Interview: Virginia Walbot

When my editor made the arrangements for this interview, Virginia Walbot said we should meet in her cornfield at Stanford University. By the time the interview ended, I understood the reason for the location. Dr. Walbot doesn't just work on corn; she feels connected to these plants in ways that make her research much more fun, insightful, and significant. A professor of biology at Stanford, Virginia Walbot represents a tradition of scientists who have found corn to be the ideal organism for answering some of the fundamental questions about genetics and development. Barbara McClintock, who passed away in 1992, discovered transposable genetic elements in corn and eventually received a Nobel Prize when biologists finally recognized the general significance of that revelation. And George Beadle, who shared a Nobel Prize with Edward Tatum for the "one gene—one enzyme" hypothesis, lived for many summers in a small house next to a cornfield—the same Stanford field where Virginia Walbot now grows her corn-so he could be close to his research plants. During our afternoon in that field, Dr. Walbot told us what her corn plants are teaching her about the genetic basis of plant development.

How did you acquire an interest in plants?

I spent some of my formative years on my family's truck farm in southern California. I was always interested in plants, always had a garden. When I was an undergraduate here at Stanford, I got very interested in the big picture of plants and plant evolution. Then for graduate study, I worked with Ian Sussex at Yale, and his lab always had a lot of people with different special interests: plant development, plant molecular biology, plant genetics. And because of these diverse influences, I could see the whole biological world through my work. And I think that's probably one of my strengths, that I see what I do in relation to a lot of bigger questions.

What does your current research have to do with this cornfield?

My lab is interested in the molecular biology of the expression of corn genes: specifically, in the details of how individual genes are regulated during plant development. There are two approaches to that problem. One is to isolate genes and then study them in the lab. The other is to make mutations, or let the plant make mutations for you, that alter the expression of the gene, and then see what the gene can do throughout the life of the plant. The real power of recombinant DNA techniques is that you can alter genes in a test tube readily and then study their behavior in some defined situation. So we look for a mutation in corn, and then we find out exactly what's wrong with it, and then we might make 10 or 20 related mutations in the lab.

Why is corn a good organism for this kind of work?

Corn is the plant where it's easiest to find mutants and study them. The big advantage of corn is very obvious if you've ever looked at a corn plant. The ear contains the embryo sacs with eggs, and the tassel contains the pollen where the sperm are. We cover each ear with a bag, so there's no exposure of eggs to stray pollen, and then we cover the tassels with bags. (We practice safe sex in the cornfield.) So every cross that's done is completely under our control, and very easy. So one corn geneticist could make, say, 300 crosses in a morning, and if each ear has a few hundred seeds on it, it's very easy to generate a population of 20, 50, 100 thousand seeds, and in a week's time you could make a million seeds. So if you're looking even for a very rare kind of event (a particular mutation, for instance), you can do it with relatively little work in corn.

This approach to corn genetics led to Barbara McClintock's discovery of transposable genetic elements (transposons) over 40 years ago, and transposons figure prominently in your current research. What are these genetic elements, and how do they affect plant development?

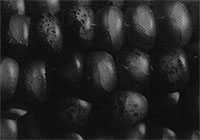

A transposable element is a segment of DNA that can cut itself out of the chromosome and reinsert itself elsewhere. So that's why they're called jumping genes. We study the transposable element family called Mutator. In corn, we can visualize the activity of the transposable element most easily when we're looking at its "cutting out" property, its ability to excise. So in these purple and beige kernels [see photograph], the beige background occurs because the transposable element is sitting in a gene required to make the purple pigment anthocyanin. And when the transposable element hops out during development of the seed tissue, then those cells can now make the anthocyanin again.

So in this case, we can think of the transposon like a genetic light switch. It's turned the gene off, and when the transposon hops out, the gene then can be turned back on, and it is easy to see the results. Transposons can hop into any part of the gene, and they can cause a gene to turn on when it's not supposed to be on, or turn it off when it's supposed to be on, and they can alter which organs a gene is expressed in.

And this is helping you answer certain questions about plant development?

The thing that really interests me is developmental timing. What's really striking about the Mutator transposons we study is that they're only active after an organ such as a leaf already begins to form. So these transposons don't affect genes until after cells in the emerging organ become committed to a particular pathway of development. And this provides a way to study a basic problem in developmental biology: What's different about a cell that still has more than one potential fate in development versus a cell that's become restricted in developmental fate (it can only become an epidermal cell, for example)? Transposons are helping us understand the timing and nature of these changes. And of course we have these wonderful color markers in corn, so we can just look at the color on the outside and detect when something happened in development. And with the continuous development of plants, we can observe these developmental events in an intact organism.

What do you mean by continuous development?

Plants are continuously making organs from scratch. So virtually every day a new leaf is made, and it goes through the entire leaf development pathway. It would be as if we were constantly sprouting arms, little arm primordia that grew into arms with fingers and everything. So during the life of the plant, we can watch development of the same type of organ over and over again in the same individual.

And this continuous development is a key difference between plants and animals?

Especially between vertebrates and flowering plants. During embryonic development of an animal such as a mammal, all of the organs and tissue types of the adult are formed in some way. And so after you're born, all you do, really, is grow. But a plant embryo is not a miniature adult plant. It consists of the first few organs of the plant, like the primary root and the first leaves, but then contained within that embryo is the plan for making subsequent organs throughout the life of the plant.

How does this difference in plant and animal development relate to the different lifestyles of these organisms?

The difference has to do with how plants and animals respond to stress and changes in their environments. Mammals, for example, can use a combination of behavior, such as flight (moving out of the way), and longer-term changes in their physiology or even development (like getting more fur when it's cold) when the environment changes. Plants, because of their cell walls, are very rigid, and they're basically stuck in place; once they've germinated, that's an irreversible place decision.

I guess behavior is the thing that plants really don't have. What they do have that animals lack completely is a profound developmental response to stress. Everybody knows if you buy a plant from a nursery where it's been growing in dim light, you get nice, dark green large leaves. But if you take that plant home and put it in a sunny spot in a window, the first thing it does is drop all those beautiful dark green leaves because it's getting excess light. And then what comes out? Little pale leaves, which are perfect for the new conditions. So the plant is able to mold its developmental outcome. It's making leaves all the time, always from the same genome, but what the actual leaf looks like is molded by the current conditions. And that degree of developmental flexibility is something that higher animals don't have.

What are some other important differences between plant and animal development?

Well, as with all the organ systems in a vertebrate animal, the germ line, the cells that will give rise to gametes, is laid down in the embryo. In plants, there is no fixed germ line. The meristems at the tips of shoots that continuously produce leaves can also make flowers where gametes will form. But they're waiting for environmental cues that say it's an appropriate season of the year or appropriate conditions to produce a flower. And so the plant can switch to reproductive development just like it can switch the different kinds of leaves that it would make over the course of a year.

The other incredibly important difference is the alternation of haploid and diploid generations in plants. In animals, the haploid cells (the egg and the sperm) are quiescent from a molecular biologist's point of view, because their characteristics are preprogrammed by the genes of their diploid precursor cells. But in plants the gametes are produced by a gametophyte, a small organism that is itself haploid. And those haploid cells of the gametophyte have to express their own genes.

This provides plants with an amazing capability that animals lack entirely. If a mutation occurs in one of us, our gametes could carry that mutation and there's no way to get rid of it if it's recessive, because the diploid precursor cell that gave rise to the gametes was able to cover for the recessive mutation. But in plants, each allele is tested in a haploid organism: the gametophyte. So the gametophyte phase and this alternation of generations, which just seems to add to the complexity of diagrams in a textbook, in fact eliminate most deleterious recessives before they can actually become fixed in a population.

This advantage of alternation of generations is critical if you think about where the gametes come from in a plant. In a mammal, the germ line is differentiated inside of the developing embryo, which in turn is inside the mother's body. So these gametes are really well shielded from cosmic radiation or whatever, and the mutation rate should be quite low. However, the shoot apical meristems of a plant have been undergoing continuous mitosis in the real world, and have been exposed to heat and cold and UV radiation from the sun, and all sorts of other potentially deleterious things. But alternation of generations culls out all of the detrimental recessives by selection acting on gametophyes. The plant genome that's passed on to the next diploid generation, the sporophyte, is not quite a clean slate, but many mutations have been removed.

How do you reconcile this idea with the existence of transposons that cause mutations in plants?

I think that because plants have this requirement to have a diverse body over time, they have a mechanism for generating diversity built into their genomes. And transposable elements provide the mechanism, particularly in corn. Plants can actually boost their mutation rate because they have a means, alternation of generations, to get rid of anything that's really bad. In fact, there are very few cases of active transposable elements in mammals, but they're just rampant in plants.

Is there any evidence that this mechanism for changing the genome is adaptive in the sense that it is a response to environmental change?

Probably the best example occurs in snapdragons, where there is a thousandfold increase in transposon events during cold stress. Barbara McClintock devoted her Nobel Prize lecture to the plant genome's response to challenge. The general drift of her remarks was that there's some kind of tolerance zone where things are relatively homeostatic for the plant, and as you get near the edge of that, you will see the breakdown of a lot of normal processes. And some of these can actually be at the level of the chromosomes. I think it's an incipient connection between genetics and physiology.

And I would say that it goes against the grain to think like this, because of Lamarck. I have given talks where people have said, you talk like someone who believes in what Lamarck said. And I don't take it as an insult, because if you look back at what Lamarck said and you think about it in modern terms, he said that the relationship between the organism and the environment matters. What he said next you may not agree with. But I think it's almost been a conviction on the part of geneticists to avoid the idea that environmental conditions could perturb the genetic process.

In ways that can actually be adaptive?

Yes. And it's the "ways that can be adaptive" part that we need to clarify. If you were a corn plant and you were under ideal conditions for corn, why mutate? So you should be very conservative. Global change comes, and that old genome, the genome that was just perfect under the old conditions, is now no longer optimal. You need a mechanism of rapid genetic change. You need evolution to happen. So the new thinking on this is not that you cause specific mutations that are adaptive, but that to adapt you need mutations. It's not that the corn plant wishes to be cold-tolerant; it's that given the genes it's got now, it never will be.

You mentioned the power of recombinant DNA methods earlier. How can cloning DNA help a developmental biologist?

A developmental biologist needs to know the progression from one stage in a cell's development to another and to divide that progression into as many small steps as possible. So you could try to understand how you get, not from Palo Alto to New York, but first from Palo Alto to San Francisco and then from San Francisco to Sacramento, and so on. One of the things that's difficult in plants is that a lot of the cell types and tissues are not very anatomically distinct over time. So there aren't that many landmarks about the developmental stage of these cells.

But with molecular biology you can clone genes that produce specific proteins that may be associated with certain stages of development. You can then use the cloned gene to develop various kinds of molecular probes for detecting the RNA or protein that appears in a cell when that gene is being expressed. And this lets you follow development over a finer scale of changes than is possible if you're just looking at cell and tissue structure. And the more stages you can tease apart, the more likely you are to get the right order of which cells are doing what and when.

Why are so many researchers using molecular methods to study plant development working on the plant called Arabidopsis?

Well, of course I love corn, but a big problem with corn is its body size. It's difficult to grow corn under highly controlled conditions throughout its life cycle. So if you want to find a temperature-sensitive mutant of flowering, for example, that's going to be really difficult in corn. But Arabidopsis is very small and it tolerates crowding really well. People are able to grow tens of thousands of plants in a tray in a growth chamber and manipulate the environmental conditions precisely. And so the real advantage of Arabidopsis for certain problems is the experimental control over the environment. And people who aren't as lucky as I am to have a field can do sophisticated plant genetics with very little space.

Also, because Arabidopsis is worked on by hundreds of people and it has a small genome, it's the logical plant to complement the Human Genome Project. It's one of the organisms being used as a model for how to assemble complete maps of a genome. In other plants like corn with a 50-times-larger genome, it would be at least 50 times more work to have this same map. But I think that any investigator needs to define carefully what their question is and then find an organism that fits. For the questions I'm asking, corn is just unrivaled as an experimental organism.

Recombinant DNA methods have also made new biotechnologies possible. How can an ability to manipulate plant genomes be applied in agriculture?

Of course, traditional plant breeding has done a pretty good job of developing crops that are very well suited to current production methods and meet our idea of, for example, what's the ideal strawberry in size and smell and shape and texture. However, given problems like pathogens or changing soil conditions, people may see that another plant species offers a solution to that problem. Biotech enables people to clone a gene from one species and move that to another species.

I think the kinds of commercial applications we'll see right away are gene transfers that confer resistance to certain diseases. Plant breeding could do that by starting from scratch and selecting for a more resistant individual, but with biotech you can circumvent the years of trying to find that gene within a species. I think the agricultural goals of biotech are really the same goals that plant breeding has always had: we want food that is better, cheaper, and safer. It's just a new toolbox and an accelerated pace of change.

Do you envision risks—environmental or otherwise—in tampering with plant genomes and moving genes from one species to another?

Personally, I think the risks are the same as they were with breeding technology. People have been manipulating other organisms for a long time. I mean, agriculture is a very old practice. The tendency when you find a plant variety that works well is to grow it exclusively, and this happens with or without biotech. But using only a few genetic variants out of the many that exist means that our food sources are more susceptible to a new disease or environmental conditions that are deleterious to that one type. So, just like with normal breeding, I think we need to ensure that there's a diversity of varieties that have any new trait. Maybe we'll turn the corner on this kind of responsibility with biotech, because now it's easier to move any gene into many varieties, rather than searching for just one variety that already possesses the trait.

Barbara McClintock came up earlier in the interview. Was she an important mentor for you?

Oh, yes. Of course for people interested in plant genetics she's ... well, after Mendel, there's Barbara. I didn't really start working with corn until I was an assistant professor at Washington University in St. Louis. The University of Missouri was two hours away, and I started collaborating with people there and learning ways to determine the timing of changes during corn development. I gave a talk at Rockefeller University when my ideas were just forming, and some of Barbara's friends heard it and told her about it, and she called me. We had a series of long phone conversations, and she invited me to come to Cold Spring Harbor. This was in the 1970s, when she was still most able to share not only the message of her work but the materials. I learned a tremendous amount from her. She was a remarkable person.

What do you think drives people like you and Barbara McClintock and other scientists to work so hard?

Well, I really like what I do. I think in terms of, you know, what did Picasso do every day? He had to clean the brushes, stretch the canvas, do all those technical things to get ready to do a great painting. And I personally enjoy all of the mechanical things, from planting the corn seed to hoeing the field. And then of course, the work itself is a never—ending story. You get to a landmark-we just cloned the autonomous element for the Mutator system after ten years of work—and you think, "Oh, that's great!" You know, we have parties, we had champagne. But then it opens up the next challenge. You don't really finish. I guess that's what I like about it.

How can our undergraduates find out if a career in science is something they would enjoy and be good at?

There's no substitute for being a summer intern in someone's lab. And I think undergraduates often miss the opportunity to find a faculty member who will hold a discussion with them every other week for an hour on some topic of mutual interest. I've done that quite a lot. The limitation is the student's asking. It's not something that faculty members can say to a class of 500: "Please come see me." I think it is the big challenge of being in college: figuring out what it is you like to do and what you're good at, and what provides you with that "Gee, I can't wait to get to work today" feeling. Who's the baseball player who said, "I can't believe they pay me to do this"? Just that feeling that you've found a perfect fit. I think for me, the more I learn about corn and the history of it, the more connected I feel with what I do. I think that's what inspires students to work hard, when they discover something they really enjoy. It's not that you have to work so hard, it's that you want to.

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc., publishing as Benjamin Cummings